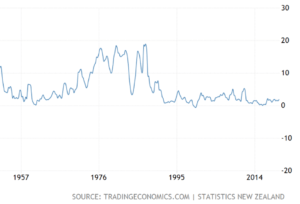

Inflation, for many New Zealanders, is either a distant memory, if they are old enough to remember it at all. It has been forty years since we have had to grapple with the curse of significant price uncertainty.

Are these days about to end?

Scarcity as a source of inflation

Throughout our economy bottlenecks are emerging. We have seen a surge in demand for some items, from hand sanitizer to podcast mics, and a collapse in demand for others, such as airline travel and restaurant meals.

We are in the early stages of a massive re-alignment of economic activity and some sectors are facing unprecedented demand. Where this demand spikes, we can expect to prices rise. In normal economic times the market would respond to these changes in prices and ramp up production. These are not normal economic times and we can expect long delays as firms struggle to change their production and distribution systems to cope with the new world order.

The food distribution system in particular is stretched as the number of outlets have been cut and many suppliers, as we recently saw with the Mad Butcher, are being forced to dump produce.

The international and domestic freight industries have been upended and we can expect delays as capacity is re-aligned.

Where choke-points rise, demand will outstrip demand and prices will respond accordingly.

Diseconomies of scale as a source of inflation

A business with a fixed overhead and five million in revenue will spread their fixed costs over all of their sales. If their sales fall to three million these costs must be shared by the reduced number of customers, making their product more expensive.

One of the great benefits of globalization has been the ability of massive factories in China to mass produce items for global scale, while countries like New Zealand devote resources to milk powder and films about Hobbits, two things the Chinese are terrible at.

The rapid decline of international trade is going to force countries like New Zealand to manufacture goods and services that we previously imported, for domestic production. If this becomes a feature of the new world order, expect the cost of these new items to be a lot higher than if we’d kept the relatively open global economy.

The helicopter drop theory of money

Milton Friedman introduced the idea of dropping cash from a helicopter to demonstrate that printing money would do nothing but increase prices, assuming that the amount of goods in the economy remained the same.

Sadly, his throwaway line has become standard monetary policy. Our own Reserve Bank has committed to printing thirty billion dollars, a full ten percent of our pre-Covid19 GDP. In an environment where our economy is shrinking, this is going to have the effect of raising prices.

Maybe.

Let’s go back to some year one economics;

MV=PQ

M = Money in the economy

V = the Velocity that the money circulates

P = the Price level

Q = the Quantity of goods and services

The Japanese have been printing vast amounts of Yen over the last two decades and have not faced any inflationary pressure, causing some to believe that Friedman was wrong. A counter argument to explain the Japanese phenomenon is that that V, the velocity of money, actually fell. Japanese pensioners horded their stash of Yen.

If a Central Bank prints vast amount of cash and gives it to Scrooge McDuck, who proceeds to store it in a huge vault, then this isn’t going to have any effect on the price level as the cash, in effect, doesn’t exist.

In the upcoming period of heightened uncertainty, this is certainly a possible outcome.

Deflation then?

During the Great Depression prices actually fell, and fell hard. We are entering a similar economic phase, possibly even more severe that the years that followed the 1929 crash.

Some asset prices, such as houses and equities, are certain to drop substantially. Traditionally these have not been included in the standard inflation calculations. Other goods, beyond the basics that are essential, will probably drop in nominal prices.

The key here is nominal prices. People who have cash are going to stop spending, repeating the Japanese experience, but as everyone’s wages and incomes fall, they will have less cash to purchase items. The number of hours you need to work to afford a washing machine may actually increase, despite the fall in prices.

So; what to expect

It is my expectation that we will re-visit the Great Depression in terms of inflation, although it is important to remember that during that period many monetary authorities actually decreased the money supply; believing that the best way to maintain a price level was to adjust the amount of money in an economy in conjunction to the level of economic activity.

It is possible that the got the cause and effect the wrong way around.

But if I am wrong…

We have pulled all of the economic levers in a random and chaotic fashion. All economic modelling becomes meaningless at this point. But one possibility is that a spike in some prices may cause a panic. If people see cauliflower jump in price today, and they fear it will continue to ramp up, they will begin to fear that their cash hoardings are about to becomes worthless.

As consumers rush to the market and outstrip the ability of suppliers to meet their demands, a price spiral will begin. The Central Bank, panicked by the resulting poverty, print more money to hand out in electronic cash, which will only fuel the cycle.

At that point we get to enjoy hyper-inflation and the economic, social and political mayhem that accompany such a development.

This is unlikely, but it isn’t beyond the realm of possibility.