Where we are now?

If the disruption created by the virus was all we had to contend with the prospects of a short period of economic malaise, followed by renewed growth, would be the order of the day. We are not so lucky. To understand the nature of the underlying problems the economy faces let’s start with the most important price in the economy; the price of money.

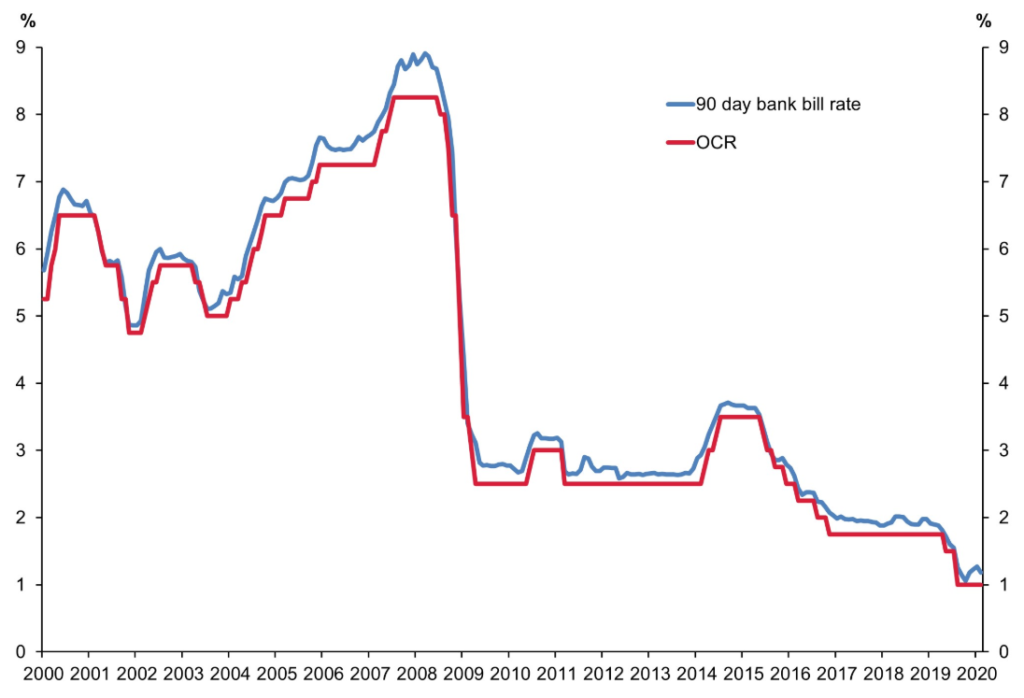

Once the GFC hit the Bank dropped the OCR down to the floor. Critically to this story, by 2013 the economy was back, humming along nicely. Governor Graeme Wheeler sought to push the rates back to a more normal level but, for reasons unclear, the long descent towards 1% began.

Adrian Orr has now dropped the OCR to a mere 0.25%.

During this period cheap money had several effects, including a surge in the price of assets, such as housing and equities. Some of this rise in values was driven by fundamentals, but much of it was the result of people seeking an economic return.

When the bank is offering deposits equal to the rate of inflation, shares and rental properties look more attractive.

The long surge in equities are perfectly captured in this graph, showing a surging New Zealand share market, that increased an incredible 30% in 2019 when our underlying economic growth was a tenth of that.

We’re all Keynesians now

Standard monetary policy, regardless if you are a follower of Milton Friedman or John Maynard Keynes, is to run loose policy during a slump and tight money supply during a boom. We ran a loose monetary policy during the Rock-Star economy of 2012 to 2019.

One of the effects of this was to drive up the consumer and commercial debt. The Key government also plunged into the red for seven straight years, clocking over sixty billion in new Crown debt. The only positive was that the purportedly conservative government inherited a very low level of fiscal debt from Dr Cullen.

Overseas nations weren’t so fortunate and have seen their debt to GDP ratios blow out to over 100% in many OECD nations during the last decade. Japan is at 240% debt to GDP, partly as a result of a falling GDP.

During this period the economic expansion of China has added export markets as well as flooding most western nations with cheap consumer and commercial products, that has helped fuel the economic furnace.

We have built an economy that is reliant on cheap money, a roaring export market to China and an endless conveyor belt of high quality and low-cost Chinese imports.

The Black Swan has Corona Virus

The problem is that even before Wuhan imploded, this economy was unsustainable. Each year the level of debt would increase at a faster rate than economic growth. Most of the lending was being funded by older savers in an endless search for yield above zero.

The only way to avoid this collapsing was for our economic growth to outstrip debt, but for this to happen the level of debt would have to actually stop growing. It never did. Some economists were starting to fret that we were building an economic bubble that was going to collapse with effects well in excess of 2008.

The real challenge facing our economic masters is how to confront one of the most significant downturns in a century without access to the usual stimulatory levers that were available as little as twelve years ago.

There is little evidence that they are up to this challenge, reverting to 2008 policies of borrow and print money that has compounded the current crisis to an unimaginable level.