It’s been over a decade since the last global downturn, and many pundits are beginning to wonder that, surely, a recession is just around the corner.

Recessions, historically, work on a ten-year cycle but it would be a mistake to assume that there is a natural decade-long economic season. We may think we are due for a downturn, but that does not mean we are going to get one. Rather, we may be facing a prolonged period of stagnation similar to what bedeviled Japan from 1995 through to 2007, and in many ways lingers on today

When the GFC hit, rather than let the economy take the pain, central banks cut interest rates and hoped that debt-fuelled economic activity would be a spur to growth. This has had some effect, but it has left our economy heavily indebted and hyper-sensitive to low interest rates.

When the global financial crisis hit the Official Cash Rate was 8.25. It has now flat-lined at 1.75. The Reserve Bank lends cash to the trading banks at 50 points above the OCR, so 2.25%. With inflation at 1.5% the cost of debt has never been cheaper.

The effect of a decade of interest rates being lower than the ethical standards of a tobacco lobbyist is people consume more debt. The effect is sobering. We have an economy that has been driven by consumers borrowing cheap money and not bothering to pay it back.

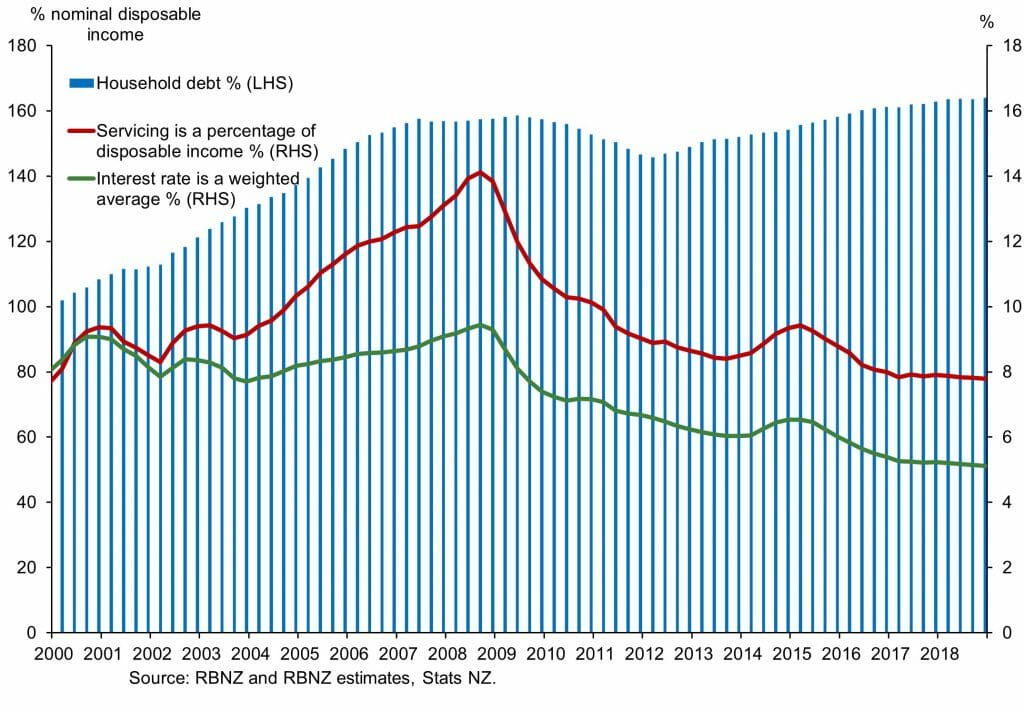

A quick look at the graph, however, shows that New Zealand consumers have considerable capacity to take on more debt. The cost of servicing the debt back in 2008 was 14% of household income. Today it is under 8%. And falling.

If we do hit a wall, there isn’t as much room for the Reserve Bank to cut rates as there was in 2008. Worse, the level of household debt continues to creep up, which means when the crash does happen, it could be messier than anything we’ve seen in the post-war period.

But this isn’t as inevitable as some pundits, and insolvency practitioners, wish. Japan is an excellent example of what can happen when the central bank runs a loose monetary policy for over a generation. Prolonged stagnation.

This is not a sustainable situation. You do not need to have a PhD in economics to appreciate this. Indeed, as Central Banks are over-run with PhD economists it’s possible that this particular qualification is a hindrance to seeing what is brutally obvious to anyone who has ever had to re-pay their overdrawn credit card bill after an epic family holiday.

Unsustainable, however, does not mean imminent. Households clearly can afford to bear a much higher debt servicing cost than they are currently burdened with and there is no hint that the Reserve Bank governor is keen to bring forward the economic dystopia that lifting the OCR back to 2008 levels would entail.